I’ll start with an excusatory line: note that I’ve written Basque-style spindle. The ones I’ve made are an adapted design (more about that later) and made in Australia… ’nuff said.

I couldn’t actually find much information about the txoatile, but Google tells us “Txoatile” comes from Basque words “txori” (bird) and “artilea” (wool), reflecting its spinning motion.

I was intrigued by the shape and wondered if it had once been made from a bone. Why? Maybe in my mind I was connecting it with the dealgan. Nothing else to suggest bone or any other material. In The World of Spindles by Beatrix Nutz there’s a link to Museotik which has a couple of examples of txatila, both in wood (and interestingly with different spellings in Spanish) and both dating from the early 20th century.

I had tried to order one from overseas, but it didn’t arrive, so I gave up. That was a few years ago. I turned to the 3D printer and in particular a reel of wood-effect PLA. To my mind it doesn’t go near to looking like real wood, but it has its uses. The original was made following the design of the authentic spindles as closely as possibly; the drop-on-the-tiles test was a failure and it broke. The next model I made with an extension in the centre. It broke, too. More filling. That one survived. The extra filling naturally gave it extra strength.

What about the shaft, with the crook at the top? This took even more playing around with angles and thicknesses, and I have a bundle of “prototypes” which may well be used as garden pegs. Getting the width right so that it would sit snugly in the whorl, but also be able to be taken out took a lot of thinking. Also, with limited 3d-related IT skills, getting smooth sides on the shaft just wasn’t going to happen. Then my knuckles were catching on the crook, so the shaft needed lengthening – more fiddling around with the width.

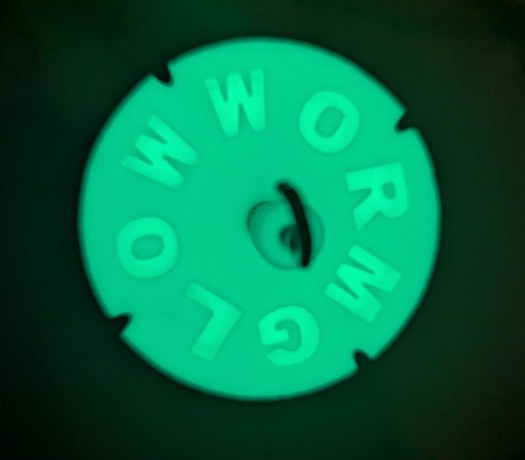

Finally, ones that are worthy of showing. Leaving it a little rough (if you start sanding the wood-effect PLA, you have to do it all over, then stain… too much unnecessary work) actually adds a touch of rustic, and it doesn’t affect usage. How about the spinning and winding on? There are a few YouTubes on this; I tried two different methods. The first was winding horizontally, the second winding up and down the shaft. If that sounds confusing, look at the photo and work from there. I find horizontal winding is quicker and without a fully-controlled experiment, I’m not sure if either method would allow for more wool on the whorl. Empty, they weigh around 53g, so I’m guessing you’d want to stop for comfort’s sake before they were entirely full.