Levisticum officinale, livèche, Liebstöckel, apio de monte, luáiste

Lovage… I first grew this in London and was happy that it grew so easily from seed, then reached a height of about 7 feet. I can’t remember using it in its first year, and then moved away from home. But it grew, and grew well.

Years later, I bought a plant in Adelaide and expected it to do equally well. It grew, but barely touched 45cm (I’m more metric these days), and this seemed to be the same for another lovage lover I know. . Hmm… I persisted, and my current plant (or group of plants, more likely) has grown to about 60cm with flowering spikes up to 1.80m and provided a fair harvest of both leaves and seeds in its third year. It’s also in a part of the garden where herbs do unsurprisingly well. Rocky soil, slightly moist and afternoon sun.

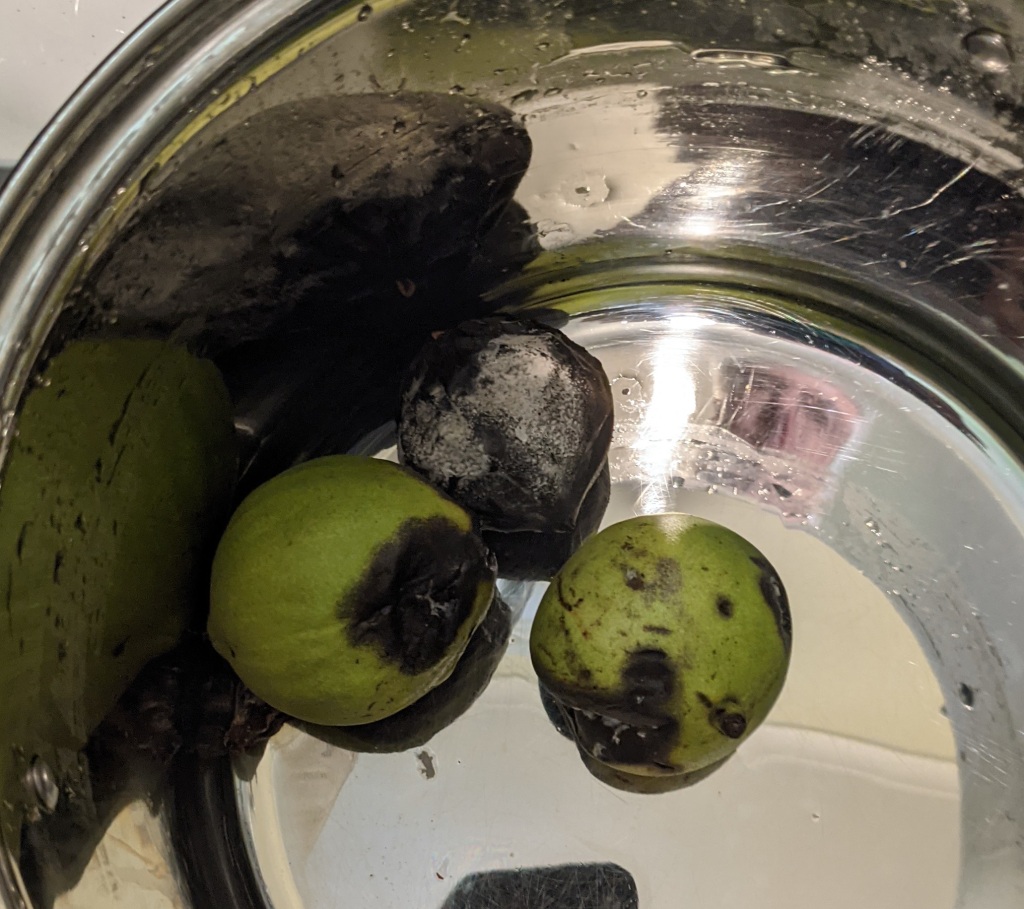

So what did I do with the harvest? Dried it. Have a look at this YouTube. Meka dries the leaves in the oven, then grinds to a powder in the blender. Easy! When I first tried drying the leaves naturally, they turned an unappetising shade of khaki. It’s still summer here, so I tried another bunch, this time grinding them when they were crisp.

Success! The powder is an attractive shade of lime (better than in the photo), like Meka’s, and extremely aromatic. I’ve used it once already, and should have enough to last until next season.

What does it taste like? If you’ve never fondled this herb before, the pungent aroma of celery is the giveaway. Strong celery. I find that some of the strength dissipates with cooking, but it’s still one to use in moderation until your experiments result in the right amount.

What’s next on the list? Spring onion greens…